On a fine afternoon in 1752, word reached King Charles III of Bourbon that his royal archeologist, Karl Weber, had discovered a treasure trove at Herculaneum. Sometime earlier, his excavation tunnels had brought to light the luxurious residence that would later be dubbed the Villa of the Papyri, however on that particular day his tunnels broke into a long porticoed garden in the villa that was filled with statuary. In the dim underground light, it was impossible to see details, but the architect dutifully sent word of his remarkable find. The king and his party, who happened to be hunting in nearby woods, rushed to the scene and set to picnicking while they waited for slaves to carry pieces to the surface.

In her book, Pompeii Awakened: A Story of Rediscovery, author Judith Harris relates what occurred next:

“Amidst a flotilla of courtiers in silks and befurred velvet finery, Charles and his Prussian wife Queen Maria Amalia arrived in a rustling, stately procession and took their seats on folding chairs. From the bowels of the earth the carved white marble group of two embracing figures, which Weber had found in the Great Peristyle, appeared at the mouth of the tunnel, borne upon a litter carried by prison labourers. A shiver of excitement rippled through the court. Already the dainty turn of that horn revealed the prized Greek look. When the whole sculpture group hoved into view two heads could be seen and two bodies. One seemed to be a man of sorts, though at closer look he wore two small horns on his head. He gazed fondly into the female’s languid marble eyes. For locked in his embrace was a female goat, surely the prettiest in the flock, whom he was in the act of penetrating.”

The king was horrified by the marble sculpture of the half-human, half-goat god Pan engaging in sex with a she-goat. He hastily led the party away from the site, ordering the sculpture to be locked in a cabinet at the Herculaneum Academy in Naples, where only those with express written permission from the King were allowed to view it. Charles’ attempt to suppress what he considered vulgar was doomed from the beginning. Prohibition fueled desire to see the erotic art and soon forgers were producing frescoes dominated by phallic figures, which were sold to tourists. Sketches of the famous Pan and the Goat sculpture were published and distributed freely. Copies were made of the most sexually explicit items. Upper class gentlemen, whose education was considered incomplete without a Grand European Tour, were soon adding Naples to their itinerary.

The discovery of such explicitly sexual pieces stunned archeologists, who had always assumed that ancient Rome was a morally upright society. Indeed, the belief that the Roman Empire fell as a result of moral depravity grew out of the discoveries of erotic art of Pompeii and Herculaneum, yet experts were puzzled that minimal evidence of a sex trade had been found in excavations of the Roman capital. The answer to this puzzle lies with the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in AD 79.

History tell us that Caligula, the third Roman Emperor, imposed a tax on prostitution in AD 40. He essentially made sex a state sanctioned business and even installed a brothel in the palace. No less depraved, Nero, who became the fifth Roman Emperor 14 years later, arranged orgies for members of the aristocracy. Smaller towns such as Pompeii and Herculaneum followed suit, mimicking society in the capital. Roman mores began to shift in AD 69, when the more conservative Vespasian rose to power but his influence was just beginning to have an effect when the volcano blew its top. Pompeii, with its 41 brothels and scores of establishments where the sex trade thrived (public baths, theaters, tabernas, and private sex clubs), was frozen in time, while the parts of the Roman Empire unaffected by the eruption evolved into a more moderate society.

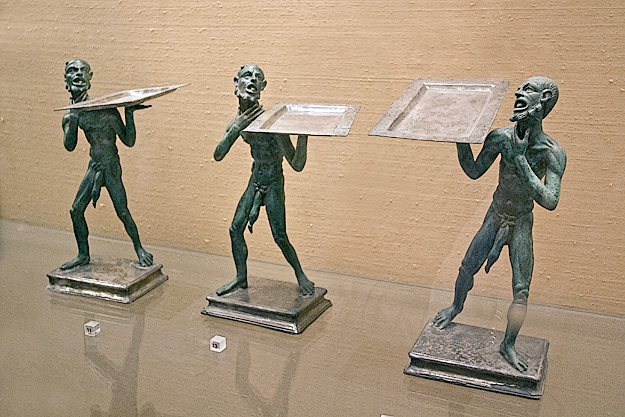

Hundreds of erotic art pieces continued to emerge from the digs during the Bourbon reign, especially at Pompeii. Frescoes of couples in various lovemaking positions, discovered on the walls of interior villa gardens, titillated banquet guests. These same guests were often gifted with amusing and suggestive penis-shaped party favors. Phallic symbols were also believed to ward off evil and ensure prosperity. Reliefs of phalluses were found mounted at the entrance to bakeries and on their ovens, while others were carved into walls and paving stones. In some cases, enormous erect penises protruded from the exterior walls of houses. As fast as they emerged, Charles locked away the vulgar items but in 1758 his successor, King Ferdinand of Naples, began allowing limited viewing by special permission. By 1819 the collection had been permanently transferred to what is today the Naples National Archaeological Museum, where it was put on public display. That more liberal stance was short lived. In 1827, two years after ascending to the throne, Francis I bowed to pressure from a priest and moved the display into a locked room, the Gabinetto Segreto (Secret Cabinet), which was opened only to “people of mature age and respected morals.”

The assemblage of erotic art remained locked away for most of the next 173 years, emerging for about a year in 1848, again in 1860 after Garibaldi defeated the Bourbons, and briefly in 1976 before it was closed for restoration. The collection languished behind locked doors until 2000, when the Secret Cabinet was finally re-opened to the general public. Viewing that was once restricted to adult men of high moral character is now open for all to see, at least those over 14 years of age. Many of the frescoes are faded and hard to see clearly in the darkened room, but even in poor lighting the subject matter is graphic, wildly sensual, and slightly disturbing, but none so much as the statue of Pan copulating with a goat.

View the Erotic Art of Pompeii and Herculaneum in the Gabinetto Segreto (Secret Cabinet) at the Naples National Archaeological Museum:

The museum is open from 9 a.m. to 7:30 p.m., with the last ticket sold at 7 p.m. It is closed on Tuesdays. The Gabinetto Segreto (Secret Cabinet) can be visited between the hours of 9 a.m. and 7 p.m., “except on Sundays during the summer months and in case of shortage of staff,” according to their website, however I suspect that hours of operation are much less structured than indicated. The Gabinetto Segreto was locked and dark on the morning I arrived, and museum staff indicated it would be closed for the remainder of the day. Two hours later I checked again and it was open. Their website also states that it is necessary to schedule a 15-minute appointment to view the erotic art of Pompeii and Herculaneum, during which you will be accompanied by a guide who will provide an explanation in either Italian or English. However, I was not required to make an appointment nor was I accompanied by a guide. Ticket prices are as follows: Full price: 8 Euro (~$11), EU citizens between the ages of 18 and 24: 4 Euro (~$5.50), and free for EU teachers and EU citizens under the age of 18 and over 65.

Subway line one stops directly in front of the museum and the Cavour stop on line two is located just a block away from the museum. Visitors should always stay aware when using public transportation when traveling, but perhaps even more so in Naples. The city’s reputation for high crime is exaggerated, but pays to watch your belongings. I found this article on The Broke Backpacker blog helpful in answering the question, “Is Naples a Safe Travel Destination.” As for me, I found the city to be no more or less dangerous than most of the thousands of cities I’ve visited around the world.