:focal(967x593:968x594)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/54/ac/54acea98-c824-411e-be32-28f465a1cb21/skull.png)

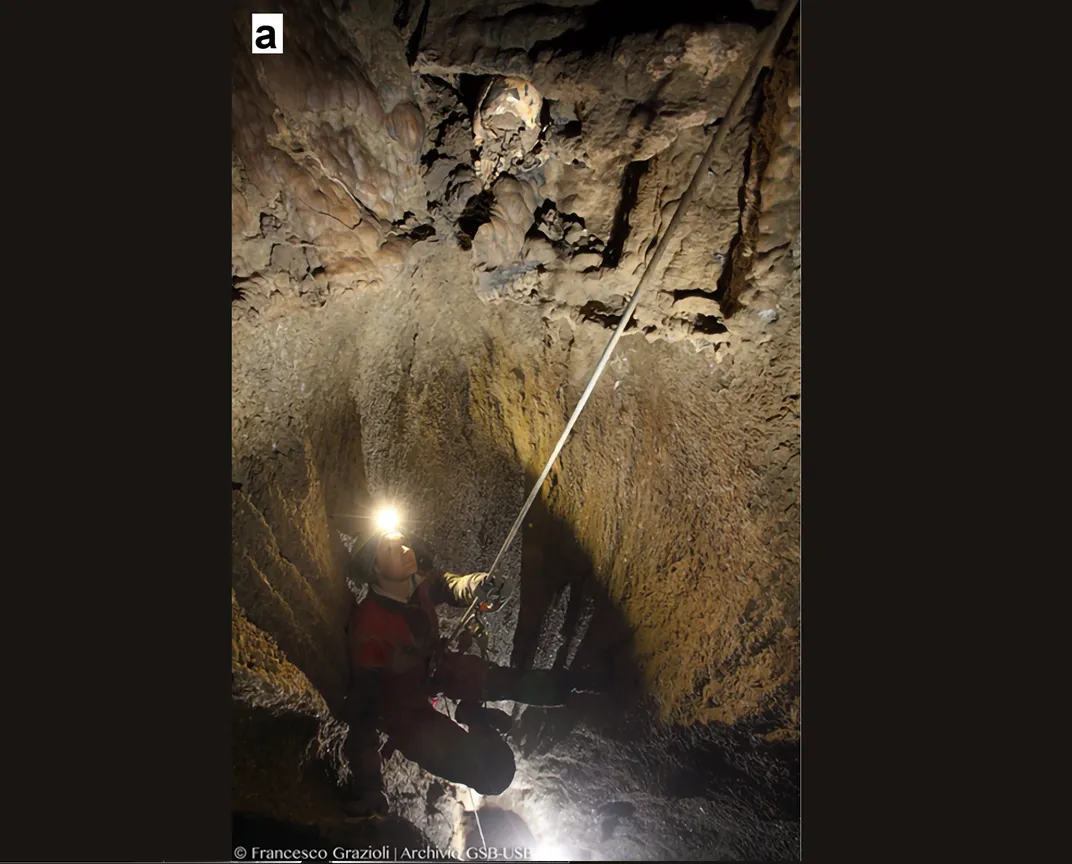

Around 5,600 years ago, a Stone Age woman died in what is now northern Italy. Archaeologists found her skull deep in the Marcel Loubens cave, at the top of a vertical shaft only accessible with special climbing equipment, in 2015. But while ancient people in the area occasionally buried their dead in caves, no other bones—whether hers or someone else’s—were recovered nearby.

Now, reports Laura Geggel for Live Science, researchers say they’ve discovered how the woman’s head ended up in that hard-to-reach space. As detailed in the journal PLOS One, the team suggests that natural forces, including opening sinkholes, mudslides and floods of water, moved it through the cave system over time.

The new findings offer a remarkable amount of detail about the ancient woman, as well as the fate of her skull after her death. Led by Maria Giovanna Belcastro, an archaeologist at the University of Bologna, the researchers found that the 24- to 35-year-old died sometime between 3630 and 3380 B.C., during Italy’s Eneolithic period, or Copper Age. As George Dvorsky notes for Gizmodo, she suffered from health problems, including nutritional deficiencies and an endocrine disorder.

Humans living in the region during the Copper Age shifted to an agricultural lifestyle marked by rising population density and an increasingly grain-based diet. This change meant more exposure to pathogens and parasites, as well as less varied sources of sustenance. Live Science reports that the skull’s owner had underdeveloped tooth enamel, suggesting childhood health problems, and cavities that may have been the result of her high-carbohydrate diet. She also had dense spots on her skull that may have been benign tumors.

Other than a missing jawbone, the skull was incredibly well preserved, enabling the authors to study it in detail with the help of microscopes, a CT scanner and a 3-D replica. The analysis found evidence of some kind of procedure, possibly a surgery, performed on the woman when she was alive. The team posits that someone applied a red ocher pigment around the injury, possibly for therapeutic or symbolic purposes.

Many of the marks on the skull date to after the woman’s death. Some seem to come from the removal of flesh from the skull—a common procedure in many ancient societies. As Garry Shaw reported for Science magazine in 2015, farmers living on Italy’s east coast 7,500 years ago removed muscle tissue from the deceased’s bones and transported them to caves for burial, possibly as part of a year-long mourning ritual.

Other damage to the skull appears to have occurred through natural processes, which also left the bones encrusted in sediment.

“After being treated and laid to rest in a burial place, the skull of this corpse rolled away, most likely moved by water and mud down the slope of a sinkhole and into the cave,” say the authors in a statement. “Later, continued sinkhole activity created the modern structure of the cave, with the bone still preserved within.”

The researchers add that the new find extends scientists’ understanding of the varied funerary practices of ancient people in the area.

Christian Meyer, a specialist in the archaeology of violence at the OsteoArchaeological Research Center in Germany who was not involved in the research, tells Live Science that “case studies like this are important to show the huge variety of postmortem episodes that can actually happen to skeletal remains, initiated by natural or anthropogenic [human-caused] factors.”